7 Strange and Mysterious Crackpot Books

When someone composes an epic fit for the times, we call that person a “genius”. When their work makes sense only within their own head, the unfortunate author is dubbed a “crank” instead. Nevertheless, cranks and crackpots often go to lavish extents to deliver their personal fantasies to the world. And there is hope within reach for all dreamers: if the resulting work is unambiguously astounding, we are forced to call the author a “genius” no matter how outlandish his subject.

Here, then, is a list of seven books which, despite or because of their difficult or unreadable text, have captured my imagination with their otherworldly images.

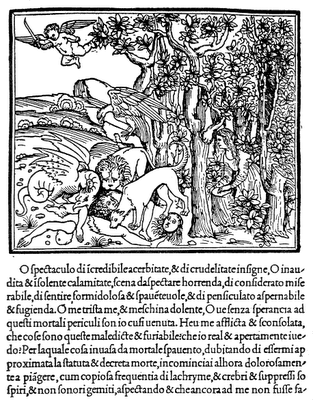

1: Hypnerotomachia Poliphilii (1499)

Long known only to antiquarians, this inexplicable incunabula was finally awarded its 15 minutes of fame with the 2004 mystery The Rule of Four. In the mass market novel (which I quite liked, despite the bad reviews), the Hypnerotomachia serves as a Dan Brown-style ciphertext with multiple layers of hidden messages, as well as the primary cause of intrigue for the collegiate team deciphering it.

The real book, although not readily revealing any more than one encrypted message, continues to bewilder with its contextual mysteries: who wrote it? why? how was it commissioned? The fact that the poem itself is meandering, obscure, and generally unreadable has not stopped scholars of all kinds from finding marvel within its pages, due to the ribald woodcut illustrations, which even today must be qualified as “not safe for work”, and unrivaled typesetting.

The poem is anonymous — as an exceptionally erotic work printed in the 15th century, it would have to be — but it is almost certainly the production of one Francesco Colonna, a Dominican monk in an era when parents would send their children to monasteries as a sort of eternal college life. No other noteworthy events or works in his life are recorded, except for an unpublished poem. Given the elaborate quality of the Hypnerotomachia and its illustrations, he must have not only labored many years but also devoted a fair share of his savings for it to appear in its present form.

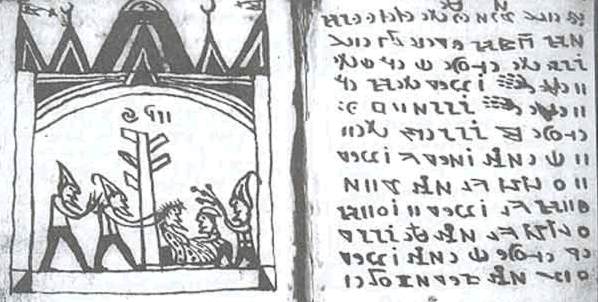

2: Voynich Manuscript (early 15th century)

This multi-subject manuscript, written in a tantalizing and possibly nonsensical undeciphered script, has attracted the interest of amateur lexicographers throughout the modern era. In the early 1600s, the occultist and polymath John Dee pored over it with no success; later, it came into the hands of the great Athanasius Kircher, and later still it became the subject of one of the first non-military uses of the computer, the 1944 First Study Group transcription of the Manuscript into machine-readable text. Despite the prolonged attention of the world’s best cryptographers, none have been able to penetrate the text, much less the enigmatic drawings of flowers, geometric designs, nude women, and so forth. The most recent theories contend that it is either in Chinese or meaningless, but both of these have their own problems. In any case, it is apparently the work of a lone individual with a talent for bizarre imagery.

3: Rohonc Codex (16th century)

The Rohonc Codex, meanwhile, has attracted several generations of would-be decipherers in Hungary, also with no success. Its illustrations seem to portray the adventures of a king and his retainers in a realm of gnostic interfaith harmony, but it was recorded in the earliest citations as a “Hungarian book of prayers”, so who knows what it’s supposed to be about? In any case, it is the only known example of its script in the world, so I am guessing that it was the work of a crackpot with a lot of time on his hands for manufacturing languages.

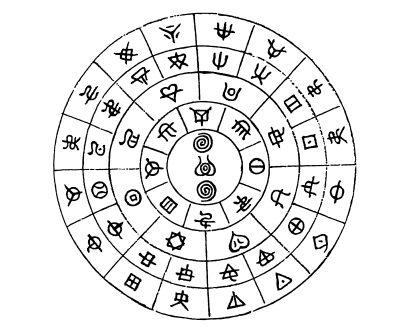

4-5: Hotsuma Tsutaye and Mikasafumi (1775?)

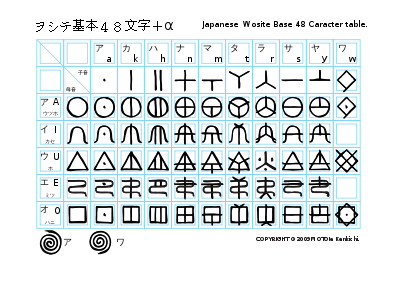

Out of nowhere in 1770s Japan appeared a series of books handwritten by an otherwise unknown person, Yasutoshi Waniko, who claimed to simply be translating into Chinese a series of ancient Japanese histories dating to 100 CE or even 800 BCE, although he boasted that the “translations” required 30 years of labor. Operating on the assumption that these books were actually forged by Waniko himself, there was some precedent for his folly; a century earlier, the Edo court had been all a-twitter about a forgery called the Kujiki Taiseikyo, which told a new history of Japan. Waniko simply raised the intrigue and awe to a new level by predating his “history” to long before Chinese writing was imported to Japan. Of course, this raises the question, how was this written down before Chinese writing? Waniko’s answer is that both the Hotsuma Tsutaye and the Mikasafumi were written in an otherwise unknown script called woshide which is either a forgotten predecessor to the Japanese syllabary or the giveaway of a clear forgery, depending on whom you’re asking.

But what interests me about the woshide books is their strict adherence to classical Japanese meter throughout their 1500-odd verses, which makes them the earliest instance of epic poetry in the Japanese language. Regardless of whether they were composed in 1775 or 100, they predate any knowledge in East Asia of Western poetic forms. Furthermore, the book is written in Old Japanese, of which very few examples survive, and is full of obscure word-forms that somewhat resemble ancient words. If it is a forgery, the author must have done intense research on Japanese linguistics, and he may have been familiar with Ainu epic songs, a century and a half before anyone else saw fit to write them down; if this is the case, what else isn’t he telling us? Or are we willing to admit the possibility that these obscure, beautiful poems date to a distant era unknown to modern historians?

These documents lay almost completely forgotten until 1966, when an amateur historian stumbled upon an excerpt in a used bookstore and made it his life’s mission to find and publish the original texts. (The Mikasafumi has only been found in excerpts, but woshide fans maintain hope.) But it can also be seen as the first in an interesting and understudied genre of Japanese literature, the parahistorical document.

6: The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinnian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion (1973)

Not so much a book as an unedited, sprawling 15,145-page manuscript in 15 volumes replete with hundreds of color illustrations, the Vivian Girls was the magnum opus of a loner named Henry Darger. It describes the rebellion by young, noble princesses from the Christian kingdom of Abbieannia against their Glandelinian abusers and flying, horned aliens called Blengigomeneans, including lengthy descriptions of carnage, torture, and various other things. Darger, who kept his work private throughout his life, had the good fortune to be a tenant in an apartment owned by “high artist” Nathan Lerner, who recognized the disheveled tomes as “outsider art” while cleaning out Darger’s room after his death. Of course, the manuscript has never been published in full, and it would probably not be worth the paper to do so. The mere fact that such a thing exists and is preserved is sufficiently eerie for my tastes.

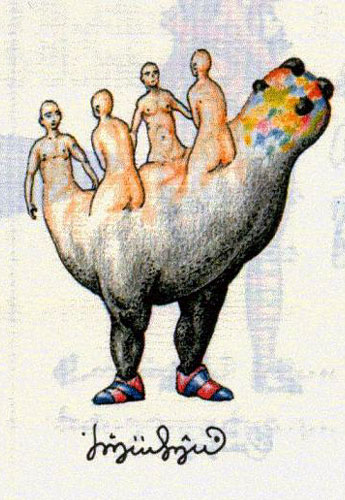

7: Codex Seraphinianus (1978)

Luigi Serafini, the author of this incredible fantasy, is still with us today, and there’s no mystery around the provenance of his book: he made it as a work of art, and intended it as a window into a strange and unknown world. Nevertheless, it is filled with a deep and strange mystery; a mixture of the familiar and foreign, it is written in an alien script that almost resembles a human language, but not quite. Many websites and articles have already attempted to give an adequate summary of the weird creatures and devices it details, and where they have failed I hesitate to attempt. In any case, I recommend this most accessible and imaginative crackpot book to anyone studious enough to find it.

Posted: June 19th, 2010 | Books 1 Comment »

[…] Avery Morrow's Internet Fancy » 7 Strange and Mysterious Crackpot Books When someone composes an epic fit for the times, we call that person a “genius”. When their work makes sense only within their own head, the unfortunate author is dubbed a “crank” instead. Nevertheless, cranks and crackpots often go to lavish extents to deliver their personal fantasies to the world. And there is hope within reach for all dreamers: if the resulting work is unambiguously astounding, we are forced to call the author a “genius” no matter how outlandish his subject. (tags: kurioses) […]