I think David Barton is a pretty cool guy. He researches the mainstream of American religious history, and doesn’t afraid of anyone.

Barton specializing in discovering facts that make atheists angry. It is misleading to respond to him with other, unrelated facts. Obviously any atheist knows that the influential Founding Father, Thomas Jefferson, was anti-Christian; and furthermore, that weird sectarians were openly tolerated from America’s earliest days, although they were sometimes driven out of mixed communities. However, that doesn’t disprove anything Barton says.

Here is is Capitol Tour video. My friend did some Snopes style fact checking, and I’ll add commentary.

His preface: “My intention isn’t to do war with the video or the message thereof, but merely to ensure that the truth is accurately portrayed. I have no idea if my sources, which include such questionable references as Wikipedia, are at all accurate. It is plain as day that the United States is a Christian country on account of the overwhelming majority of her citizens who profess that faith. The attempt to baptize the largely Masonic founding fathers is misguided nevertheless, and the attempt to appeal to the original intent of the framers represents the most appalling tendencies in American politics.”

Claim 1: Congress printed a bible for school use. (0:41)

Fact: The Aitken Bible was endorsed by Congress, but printed by Robert Aitken, a Philadelphia-based Scots printer in response to the embargo on the colonies during the Revolutionary War. There is no mention of it being for school use, although it was common for the Bible to be used in schools at the time. (Source: Wikipedia)

Avery’s analysis: At this time in Western history, printing a Bible was such a major undertaking that securing assistance from one’s government was standard, if not necessary. On the other hand, Congress was expressing approval and affirmation of the Bible, and George Washington added: “It would have pleased me well, if Congress had been pleased to make such an important present to the brave fellows [veterans of the Revolutionary War], who have done so much for the security of their Country’s rights and establishment.” So I’ll rank this one Mostly True

Claim 2: Capitol rotunda paintings “recapture Christian history of the United States.” (1:27)

Fact: “Christian” means something closer “European” in this context. It is true that the paintings depict religious scenes. The term “Christian history” is only provided for contrast with the Native history. (Source: common sense)

Avery’s analysis: I’m going to have to say, though, that the baptism of Pocahontas wasn’t exactly a seminal moment in American history. It’s good to draw attention to the link between Christianity and civilization in these paintings. Ranking: True

Claim 3: The U.S. Capitol was used as a church building under the orders of Vice-President Thomas Jefferson. External churches were permitted to hold services in the old House room and the Marine Corps band was used for some of them. Thomas Jefferson regularly attended church in the Capitol. (2:26)

Fact: This is actually 100% factually accurate, but T.J.’s sentiments on such basic articles of Christian faith like the divinity of Christ and the importance of the Bible are well known. Most of the founding fathers only externally presented themselves as Protestants and in fact hewed to the Masonic religion privately. (Source: Library of Congress website)

Avery’s analysis: T.J.’s church attendance despite this only emphasizes the role of Christianity in the early 19th c. Ranking: True

Claim 4: President Garfield used to be a minister, and furthermore one quarter of the statues in the rotunda are ministers. (5:02)

Fact: James A. Garfield had an eclectic career before he went into politics, including a stint as a minister, which he reportedly disliked. According to the Capitol Architect website, the rotunda contains statues of Presidents Lincoln, Eisenhower, Garfield, Grant, Jackson, Jefferson, Reagan, and Washington, as well as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Secretary Alexander Hamilton, nine statues in all. King and Garfield were ministers— one-quarter of nine is two and one-quarter. (Source: Wikipedia, Architect of the Capitol Website)

Avery’s analysis: Barton supporters will be hard pressed to show me the extra 1/4 of a person. This is stretching the facts. Ranking: Barely True

Claim 5: Thomas Jefferson authorized federal funds for missionaries and church construction as part of a treaty with the Kaskasia. (6:56)

Fact: Actual text is “Whereas, The greater part of the said tribe have been baptised and received into the Catholic church to which they are much attached, the United States will give annually for seven years one hundred dollars towards the support of a priest of that religion, who will engage to perform for the said tribe the duties of his office and also to instruct as many of their children as possible in the rudiments of literature. And the United States will further give the sum of three hundred dollars to assist the said tribe in the erection of a church.” (Source: Oklahoma State Digital Library, Treaty with the Kaskaskia, 1803, Article 3)

Avery’s analysis: Here, again, Christianity is synonymous with civilization. It is often forgotten that this is so. Even 20th century Japan, hardly a Christian state, funded Christian missionaries in the South Pacific. Ranking: Mostly True

Claim 6: Twenty-nine of the fifty-six signers of the declaration of independence held seminary or “bible school” degrees. (7:12)

Fact: All colleges at the time were what we would consider today seminaries. (Source: my 7th grade history teacher)

Avery’s analysis: Indeed. Harvard Divinity School is hardly Bob Jones. This is only Half True

Posted: February 26th, 2011 | Secular-Religious

I just watched yet another program on Ninomiya Sontoku, aka Kinjiro, that considers him as a statue. Schools throughout Japan have Kinjiro statues, as do some other institutions and many private individuals. These statues were handed down from previous generations and most people don’t quite know who Kinjiro was besides someone who read a lot of books. I know some variety shows do discuss him as an actual person, but they seem to mostly rattle off stats and figures and argue over whether he was a bureaucrat or an economist, or some asinine thing. I’ve never heard anyone tell the following story:

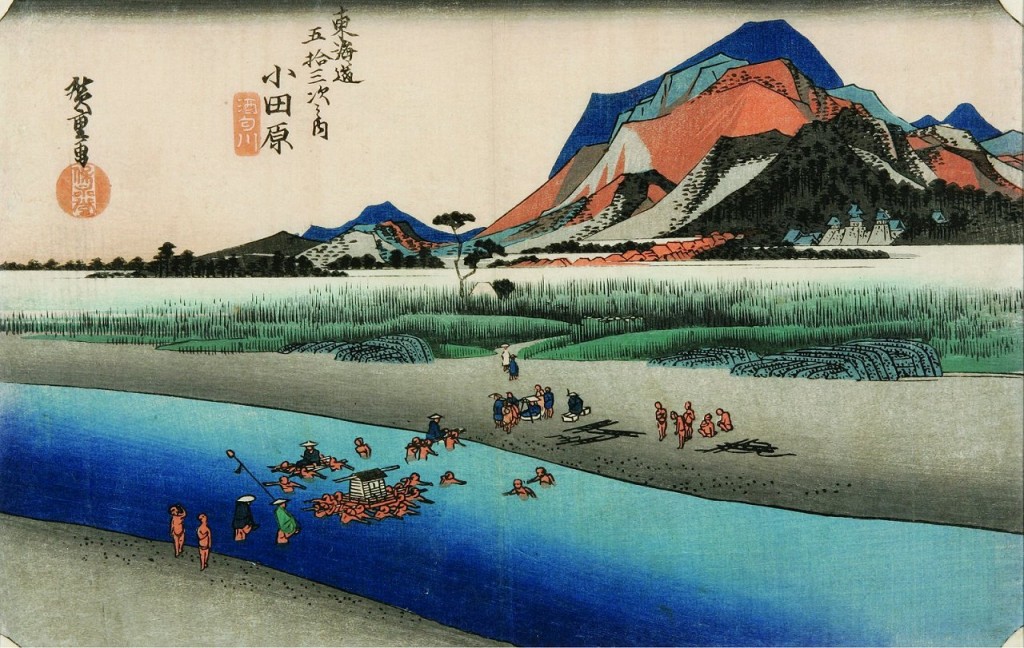

When Kinjiro was born, the family were really in hard straits. To add to their distress, when Kinjiro was five years old, the Sa[kawa] River overflowed its banks and washed away his father’s land, leaving them in abject poverty.

[…]

When Kinjiro was about twelve years of age, he went to work for a year with a farmer in the neighborhood. At the end of the year, before starting for home, he received, in addition to his board and lodging, a Japanese kimono and about two yen. His mother expected him early and was waiting for him, but when at night he had not returned, she became quite anxious. Shortly after dark he came rushing in, all out of breath, and full of excitement. When his mother reproved him for being late, he told her that in the morning he had received from his master a kimono and two yen, and had immediately set out for home. On the way he had met a man with a lot of little pine trees for sale. The poor man was very disheartened, because he had not succeeded in selling a single tree, and told Kinjiro that unless he could find a buyer he would be very much distressed. Kinjiro was sorry for the man, and an idea struck him whereby he could not only help the man, but could at the same time do the whole community a good service. As we already know, the Sa[kawa] River sometimes overflowed its banks. Kinjiro thought if a couple of rows of pine trees were planted along the banks of the river, and once took root, it would remedy this difficulty. So he bought all the trees and spent the remainder of the day planting them. He felt sure his work would have its reward. To-day those trees are large, and not only support the river bank, but add much to the beauty of the scenery. They stand as a living monument of little Kinjiro’s thoughtfulness.

“Just before the dawn: the life and work of Ninomiya Sontoku” by Robert Cornell Armstrong (1912)

Let’s put aside the fact that Kinjiro gave the fruits of a year’s labor to save a local farmer. What is clear is that the problem Kinjiro solved is one that was also faced by the people of Japan in the 1960s. Rivers in Japan frequently overflow and damage riverside structures. Or, at least, they used to. Nearly all the rivers in Japan have been filled in completely with concrete. Nobody ever thought to plant multiple rows of trees on the riverbanks. The Sakawa River itself has been dammed, and Kinjiro’s surviving trees were almost chopped down by thoughtless bureaucrats; the townspeople saved them.

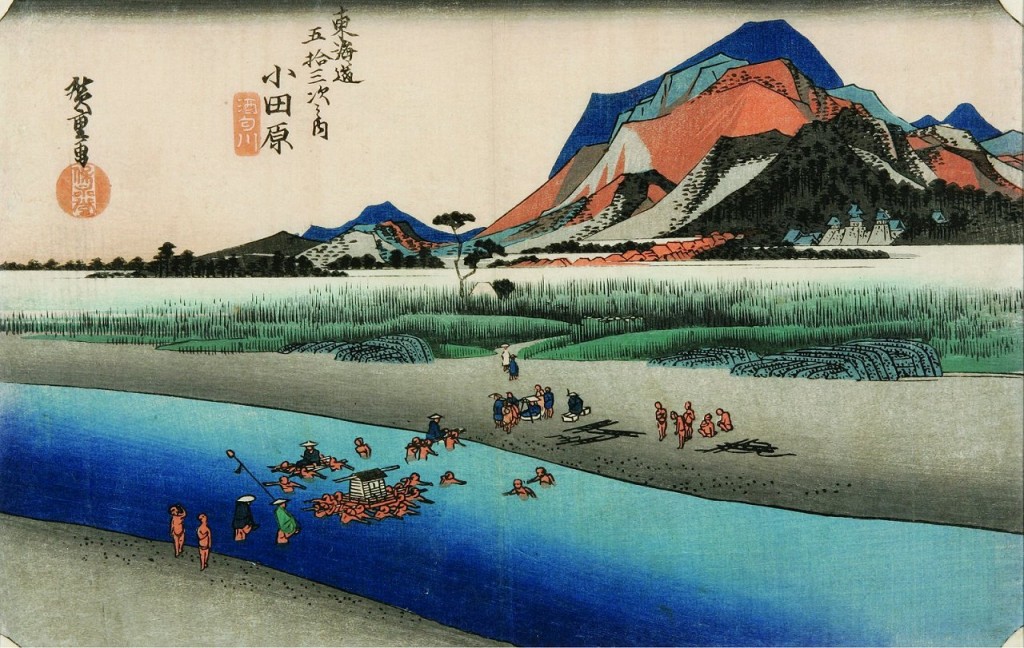

Kinjiro was beloved by the people of his area because of his wisdom and his big heart. The people of Odawara City where he was born still remember him fondly today, referring to him as “Sontoku-sama”, and honoring the trees he planted there. A few websites therefore relate the story of the planting, but nobody seems to have made this connection with the state of Japan’s rivers today. Would that we had more like Kinjiro, and fewer building statues of him.

Posted: February 11th, 2011 | Kokoro

The Covenant

James A. Michener

Fawcett, 1987 (Amazon)

I think the question I really wanted this book to answer for me is why District 9 is such a good movie. It outperformed expectations.

Michener, who is renowned for his expert research, brings us all of the most important episodes of South African history, and many of its most telling quirks–the Norwegians who fought and died in the Boer War purely out of hatred for imperialism, the Afrikaner housewives who demanded that a classical statue in their town square be veiled in the name of decency–all in the context of an epic, generation-spanning fictional narrative, the purpose of which is not to distract from the history being made, but to give that history a human face. Michener’s is determined to show what history looks like, at the expense of any side; and, digesting the work properly, you are forced to evaluate the morality of remembrance and history itself as a human endeavor.

Michener opens with the imagined stories of the !Kung San and Zimbabweans before proceeding to the meat of the narrative, the Afrikaners. Taking the three stories side by side, it is impossible not to come to a reasonable evaluation: the !Kung San’s culture was beautiful and timeless, but being timeless it was also unchanging, and did not have any cultural narrative that could fill up a 1000 page book. Zimbabwe, too, must have had some limited history in the days of its kingdom, but it was never written down and dissolved into legend, irrelevant to its descendants. Is that bad, necessarily? Is it better to have a collective history than a lot of individual stories? Well, the next section will supply some evidence.

The Dutch are deposited in Africa as an unimportant colony, and remain unimportant in world history to everyone besides the southern Africans themselves– attracting notice only as the heroes of the Boer War and the villains of apartheid, but never with any context, and always as part of some other country’s political narrative. In an utterly foreign and savage land, being given no meaning to their mission, it was natural that they would invent some meaning for themselves, and Michener’s quiet argument in The Covenant is that they became an Old Testament people fashioning themselves after the narrative of the ancient Israelites.

This may or may not be true. But the more obvious truth is that they clung to every event in their history, with a bitter, collective insistence that they were alone in the African wilderness–other ethnic groups being incidental or antagonistic to their racial memory–and had been attacked on all sides for hundreds of years. For much of their history the Afrikaners were pretty much left alone to populate the coastline, embark on their own Oregon Trails, and rough it in the Veld with no formidable enemy but themselves. But after their colony was appropriated by the British Empire, Afrikaners kept a running tally of the English crimes against them, which, combined with post-independence responses to apartheid, were made into a historical case for the brutality of the world against the Afrikaner: a double hanging at a place called Slagter’s Nek, the imposed end of slavery by the English, decades of fighting the English for freedom, torture and death in English concentration camps, and now the murders of innocent citizens by (black) communists and killers, political harassment by European leftists and atheists, and so forth.

Too much history! Of course, this history is not easy to forget, just as Americans cannot easily forget 9/11. The Afrikaners cannot be faulted for remembering things that happened to them as a people. If we are to fault anything, it is human nature. Should someone time travel to 1700 and warn the Afrikaners that race is a cultural construct and that they should intermarry freely with the natives, they would be lynched; this was a group that already shared so many cultural bonds separating them from the Other that race was just another layer on the pile. Michener laments many times that the Afrikaners did not give the Colored (mixed-race and Indian) population equal voting and political rights, a choice that could have prevented the terrible legacy of apartheid and could have even eventually integrated the black population. But excluding the Colored was more than a matter of race. In the Colored population the myth of embattled Christians stranded in the wilderness was diluted and lost, replaced with family and local histories that held none of the power of racial memory. Putting aside the Afrikaners who were labeled Colored as a brutal punishment, the actual Colored population did not share the Afrikaners’ teleological drive.

Out of the evils of human history, some, such as imperialism or Balkans-style ethnic conflict, are readily understood as the mistakes of good people. Some, like Nazism and slavery, were easy to understand as the product of good people in the past, but are steadily moving towards ineffability as the world alienates itself from the motives behind them. And some, like apartheid, are simply bizarre to an outside observer. How could a tiny minority of good people perpetrate a system like this onto people they were at peace with, their neighbors and coworkers, whom they agreed belonged in their country? The answer can be found precisely in the Afrikaner narrative, for a people battling for their lives against a cold and uncaring world cannot easily incorporate other peoples, who do not share that sense of urgency, into their polity. The Afrikaners of the 20th century did not lack humanity or intelligence. They openly discussed their political situation with visitors of all kinds; their politicians, leaders, and judges constantly tried to impress the importance of their narrative onto South Africa’s other ethnic groups. The only thing they lacked was the ability to escape their Afrikaner identity.

What actually dissolved over the course of the 20th century was their belief in their own coherence. When they finally backed down and admitted that their system did not work, they were also being forced to admit that their own narrative, which could fill not only the 1000 pages of this book but several more books, was unable to provide a basis for fair and just government. The government that replaced them did not have a 1000-page narrative. In fact, we can see that while it is fairer to everyone, it is also directionless, and from this lack of meaning rises selfishness, corruption, and anarchy.

So, why is District 9 a good movie? Because the Afrikaners are us: a species struggling to keep the world coherent in the face of chaos. We have developed in the past 500 years the ability to refine our myths, but an educated person cannot help but notice that even these purified, enlightened narratives fail to change basic human nature. So we paddle against the current, and hope that if the aliens come they will be saviors, and not miserable wretches like us.

Posted: February 3rd, 2011 | Book Reviews