Protected: 日本人のヘンな「日本人のヘンな英語」 David A. Thayne’s Scam on the Japanese People

Posted: February 29th, 2012 | Japan Enter your password to view comments.

Posted: February 29th, 2012 | Japan Enter your password to view comments.

His Majesty the Emperor of Japan has an interest in goby taxonomy. Because this is part of the Emperor’s private life, it is not a subject of huge interest in Japan, although it gets a prominent mention in his Wikipedia biography. The Imperial Household Agency has compiled a list of his scientific papers on the subject. Here are some key points:

I think there is an interesting point to be made in the fact that Prince Charles has spent his free time designing and marketing a line of homeopathic sugar pills while Prince Akihito made legitimate contributions to science.

Posted: February 17th, 2012 | Japan 1 Comment »

Every day, Longreads and Longform post long, well-researched articles. But sometimes people write whole books and just post them to the Web, which apparently are too long even for these sites. Here are some great non-fiction, fascinating e-books that are free to download.

The Great Internet Conspiracy: The Role of Technology and Social Media in the 9/11 Truth Movement

The Boy Who Cried Wolf is, in modern parlance, a simple “troll.” He delights in posting inflammatory material in public spaces to cause unnecessary concern, and he then laughs at the angry reactions he provokes. In the fable, he only gets away with this once before his village brands him as a troublesome nut. The rest quickly ignore him, leaving him to experience poetic justice in short order. But on the Internet, this could not happen.

With social media at his fingertips, the Boy’s alarm message would spread well beyond his village. Some people would find his initial posting at once, while others would find it much later. A few would accidentally revive it years after the fact. But to pick a time at random, say one week after he had his fun, both the initial “fake” alert and the later “real” warning would be available simultaneously, with no way to predict which would be more widespread and more likely to come up on a search engine. Both would also be mixed in with a bewildering array of angry posts, some by people who had been duped, others noting that he was actually right.

The Broken Buddha: Critical Reflections on Theravada and a Plea for a New Buddhism (Some knowledge of Theravada Buddhism is a must.)

A man I know attended a Thai temple in Singapore for fifteen years before becoming one of my students. He could chant the five Precepts but couldn’t name any of them and didn’t know that what he was chanting referred to morality. He did know however, that every time he went to the temple that he should give an hung pow (monetary donation) to the monks. Young well-educated Asians have often told me that they got their first real understanding of Dhamma when they joined a Buddhist group at the university where they were studying in the West…

Esperanto is sometimes criticized for using compound words where a “real” or “natural” language would have a “real” word. What constitutes a “real” word, as distinct from a compound word, turns out not always to be apparent to such critics. One Esperantist reported the case of a woman who, informed of the use of mal- to create antonyms, cried out in dismay: “You mean Esperanto has no basic word for unhappy?”

Posted: February 13th, 2012 | Books, Dharma

Or, “Japanese leftist groups are horrible”.

June 30, 1974

A group of students calling themselves the “Buraku Liberation Study Group” request permission to form as a school club at Yoka High School, superseding the existing “Buraku Issues Study Group”. The reason for this name change is debated:

The Buraku Liberation League claims that the previous “study group” was ineffective at combating widespread bigotry and a new group was necessary.

The Japanese Communist Party claims that the Buraku Liberation League was pushing students to “come out” as burakumin and to engage in political activism within an official school club, which is illegal at Japanese public schools.

July 30, 1974

The “Buraku Liberation Study Group” is approved by the headmaster and vice headmaster, but not by the school. The reason for this disapproval is debated:

The Buraku Liberation League claims that the teachers at the school were universally opposed to the new group because of their bigotry.

The Japanese Communist Party claims that members of the “Buraku Liberation Study Group” were bullying other students, “impeaching” them, and making them confess to “crimes” against burakumin, and the teachers were opposed to a club that would facilitate this.

July-November

“Buraku Liberation Study Group” students hold over a dozen meetings with teachers.

November 18

“Buraku Liberation Study Group” students begin a sit-in in front of the teacher’s room.

The Japanese Communist Party claims that “Buraku Liberation Study Group” students were pressuring teachers to admit wrongdoing.

The Japanese Communist Party claims that the Buraku Liberation League filled six trucks with supporters and drove them inside the school gates to hold a demonstration.

The Buraku Liberation League claims that “concerned members of the League and PTA” were gathering at the school gate.

November 19

Teachers at Yoka High School move into group housing and begin carpooling to school in a shared bus.

The Buraku Liberation League claims that the Japanese Communist Party forced the teachers to move in together to prevent “defections”.

The Japanese Communist Party claims that members of the Buraku Liberation League were threatening teachers and they moved in together to ensure the safety of their families.

The Japanese Communist Party claims that police were informed about these threats but declined to act.

November 20

The Japanese Communist Party claims that the Buraku Liberation League occupied a school office and formed a “Joint Struggle Committee for the Impeachment of Discriminatory Education”, and “Buraku Liberation Study Group” students went through the school announcing the names of teachers who needed to be “impeached”.

The Japanese Communist Party claims that police were informed about these threats but declined to act.

November 21

The leader of the local branch of the Buraku Liberation League (Yoshiaki Maruo 丸尾良昭) enters the teacher’s room and threatens the teachers, then goes outside and tells the student body that he will never resort to violence. After this, he joins the entire League marching through the main streets of Yoka City in a show of strength.

The Buraku Liberation League’s account does not explain how this happened or what was going on during this time period.

November 22, 10:00AM

Classes are canceled and the teachers attempt to leave the school.

The Buraku Liberation League claims that teachers instructed students to yell “drop dead Buraku scum” at Buraku Liberation League activists standing outside the gates.

The Japanese Communist Party claims that no students said any such thing.

The Buraku Liberation League claims that there was a struggle, and “some on both sides” were injured.

The Japanese Communist Party claims that many teachers were injured, but no one from the Buraku Liberation League was taken to hospital.

November 22, 11:00AM

Remaining students flee the school.

The Japanese Communist Party claims that teachers who had not been beaten unconscious are at this point physically dragged back into the school.

The Buraku Liberation League claims that teachers had an extended dialogue outside the gates and were “persuaded” to return to the school.

The Buraku Liberation League claims that the Japanese Communist Party instructed teachers to leave the school, and that a memo was found instructing the teachers on how to behave.

The Japanese Communist Party claims that this memo was fabricated by the Buraku Liberation League.

November 22, 11:00AM-1:00AM

According to the findings of the Japanese Supreme Court, during this entire period of thirteen hours, the teachers of Yoka High School, including many women and old men, were confined to the clubroom of the unapproved “Buraku Liberation Study Group”, where instruments of torture had apparently been prepared for this day. They were verbally assaulted, beaten, strangled, had buckets of filth poured on their heads, had spoiled milk poured into their shirts, had their heads locked and punched, had tobacco butts put out on their faces, and were threatened with further violence and death.

The Buraku Liberation League’s account does not explain how this happened or what was going on during this time period.

November 22, roughly 11:00AM-12:30PM

The student council of Yoka High School enters the central office of the city police and reports a crime in progress. The police respond that they are uninterested in investigating.

The students confer, and apply for and receive a permit to protest on a section of riverbank in the center of the city from 1PM to 5PM.

November 22, 1:00PM

The roughly 1,000 students who had fled the school assemble on the riverbank and begin chanting, “Give us back our teachers!” and “Stop the violence!”

A black van owned by the Buraku Liberation League suddenly appears, playing the Liberation Anthem, and blasts through its megaphone that the protest is an act of ugly discrimination and racism. Students yell back at the van.

November 22, 3:00PM

The leader of the local branch of the Buraku Liberation League (Yoshiaki Maruo 丸尾良昭) personally appears at the protest and intimidates some of the students. The students ask him why he promised them no violence; he responds that some things just happen, and that anyway they brought the violence on themselves.

November 22, 5:00PM

Students stand on their permitted section of riverbank until 5PM, calling “Give us back our teachers!” and singing the school anthem. This area is now known to locals as the “Square of Courage”.

A “meeting” is held in the school gymnasium by members of the Buraku Liberation League to “impeach discriminatory education”.

Twenty-three teachers write self-criticisms at the request of the Buraku Liberation League.

November 23, 1:00AM

Sixty teachers arrive at the local hospital with injuries; forty-eight are seriously injured and are admitted for extended treatment. Masatoshi Katayama, the most seriously injured, has had his ribs and hips broken in several places.

The Buraku Liberation League’s account does not explain how this happened or what was going on during this time period.

It is not clear what the city police were doing at this time.

December 1

Thirteen members of the Buraku Liberation League are arrested.

17,500 residents of Yoka City hold a meeting to discuss how the city and school can prevent further violence by Yoshiaki Maruo and his gang.

1975

The Japanese Communist Party’s favored candidate for mayor wins election in Yoka City.

Students allied with the “Buraku Liberation Study Group”, who are continuing to meet in their clubroom despite lack of official approval, inform the Buraku Liberation League that they are not experiencing any active discrimination at school, but that teachers sometimes glare at them and this makes them feel uncomfortable.

1975-1995

The wheels of Japanese justice churn. Slowly.

1996

The thirteen arrested League members lose their Supreme Court appeal and are ordered to pay 30 million yen ($300,000) to the injured teachers.

2007

Yoshiaki Maruo founds a “Buraku Liberation and Human Rights Network” in Hyogo Prefecture.

Posted: February 12th, 2012 | Politics 3 Comments »

I remember reading once about a “town that doesn’t exist on a Japanese map”, where burakumin live. As far as I can tell this was the fancy of some anti-Japanese writer. Still, the idea intrigued me, so I went and scoured the Japanese Web for a list of private residences that don’t exist on maps. Most hisabetsu buraku, old untouchable hamlets, have vanished from town borders and are now replaced with ordinary, nice little suburbs. But on this list, there are a few oddball places that I can’t explain from the information available on the Internet.

Please cue the X-Files theme for whenever you see that a hamlet really has no official name.

Posted: February 8th, 2012 | Japan 3 Comments »

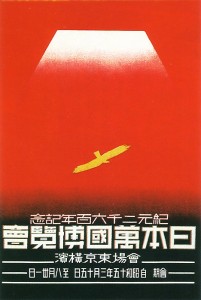

Kenneth J. Ruoff in Imperial Japan at Its Zenith did an in-depth study of the year 2600 (that’s 1940 to you Westerners) but neglected to mention the World’s Fair that Japan had planned for that year. It was to have been a grand affair on the Tokyo seaside, running from March 15 to August 31. But like the Japan Olympics planned for that year, World War II put a damper on things. This was all the more unfortunate because the World’s Fair committee had already begun raising funds for the event by selling 10-yen tickets, which equates to a large amount of money today, something like 50 to 100 US dollars.

A collective duty was felt that these tickets must not become useless– a duty which apparently extended beyond reasonable lengths of time. When the city of Osaka held its World Expo in 1970, organizers accepted tickets to the cancelled 1940 World’s Fair as permitting free entry to their own event! They didn’t even take the antiques, they just inspected them and gave them back with a complimentary entry ticket. And when Aichi held a World’s Fair in 2005, they did the same! Apparently as many as 90 tickets from 1940 were used to gain access to Aichi in 2005– to this, Japanese Wikipedia adds the obligatory disclaimer, “citation needed”.

The tickets now sell for over $200 on Yahoo Auctions, but that could be a bargain, depending on how many Japan World’s Fairs you and your descendants are planning on attending.

Posted: February 6th, 2012 | Japan

Below, I translate an article by Nobuo Ikeda, Japanese economist and noted commentator on nuclear issues in the Japan blogosphere. This article and its translation are released under a Creative Commons BY-NC license.

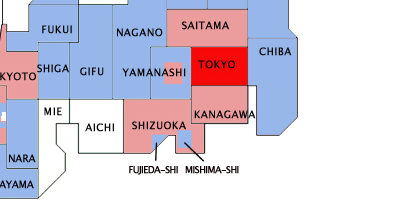

I thought that opposition to nuclear power is not about individual concerns but an overriding sense of “moral duty”, but it seems like recently it’s shown itself to be simple selfishness. The local citizens’ brigade to “halt the scattering of radiation” list the towns and cities which have received rubble from the earthquake as part of an effort to stop all rubble from being buried.

As explained by Taro Kono, most of the areas devastated by the tsunami were unaffected by the Fukushima Daiichi accident and it thus makes no sense to refuse all rubble from Tohoku. The radiation in most of Tohoku is no different from Tokyo or Yokohama. Without the ability to clear the rubble and dirt from Tohoku, the reconstruction of the affected areas will hit a brick wall. Even Osaka City Mayor Hashimoto, who was stirring up fears about radiation last year, agrees that rubble does not have any problematic level of radiation.

On this citizens’ brigade website, there is a “doctor’s written opinion on accepting rubble into your hometown” which states that “regulations must be strengthened to 10 becquerels per kilogram”. The basis of this is an article written by one Yuri Bandashevsk. Cesium-137 is said to cause “functional modifications in the cardiovascular, nervous, endocrine, immune, reproductive, digestive, urinary excretion and hepatic system,” but the only evidence given for this is experiments made on rats! [Actually, if you merely glance at the linked article, you’ll see that Mr. Bandashevsk is clearly unqualified to do this kind of evaluation. –Avery]

Zero-risk fundamentalism like this makes it impossible to evaluate risk quantitatively. Looking at a page like this, you might be led to believe that “radioactive pollution is worse than an atomic bomb”, but in fact Fukushima Prefecture found that 99.8% of residents of evacuated areas will receive a real dose of less than 1 millisievert throughout their lifetime. I’d like to see the three self-styled physicists who wrote this opinion make a quantitative evaluation of the effects of 1 millisievert of radiation over a span of 50 years.

The anti-nuclear movement claims the great moral duty of protecting the environment, but trying to block the importation of rubble has nothing to do with this moral duty, but is rather based in the selfish principle, “I don’t care what happens to the victims of the tsunami, but I want zero risk in my backyard.” Yukio Hayakawa and Kunihiko Takeda, who torment an entire prefecture with vitriol like “Fukushima’s produce is poison,” operate on the same principle. When the movement becomes this depraved it is only a matter of time before it dissolves entirely.

Posted: February 5th, 2012 | Japan 1 Comment »

The 32nd issue of “Kikan Kiyomizu“, published in the 9th month of the 7th year of Heisei, is a special edition on “70 years of Kiyomizu City and Toda Bookstore”, containing an article entitled “Memoirs of 70 Years of Toda Bookstore” published by the former chief librarian of Kiyomizu City Public Library, Harumori Yamanashi, in which we may read the following description of a bookstore ship.

One final scene which resides in my heart is that of a small boat which sat at the bend in the river afore the household of Shin’ichi Shibano loaded up completely with what appeared to be brand-new books. It was a perfect subject for photos and indeed seemed quite an appropriate motif for a port city.

The bookstore, which swayed gently with the ripples on the river, was one of my Kiyomizu rediscoveries. I later learned that it was made for the fisherfolk who went out to the ocean for many long, idle hours at a time, and who had thus requested such a bookstore ship.

A bookstore ship swaying on the river would be a picture of some grace, and I imagine if we were to search for photographs we might still find some remaining. It’s a sight I’d like to see.

Translated overliterally from the Jinbo Town Nerd’s Diary.

Posted: February 4th, 2012 | Japan

Reading Whittaker Chambers’ Witness for the first time, I was intrigued by his mention of an innocent Japanese college student swept up by the Communist underground in America. Hideo Noda (野田英夫, 1908-1939), nephew of the peace-loving socialist politician Prince Fumimaro Konoye and student of Diego Rivera, was a warm-hearted and talented man apparently drawn to Communism by a genuine sympathy with the poor. You can see in his 1933 work Scottsboro Boys (pictured) a portrayal of working-class urban life that should be familiar to any visitor to an American city. After a discussion with Chambers, Noda eagerly agreed “to go to Japan to work as a Soviet underground agent”, although Chambers does not make it clear if Noda realized that this work would involve espionage.

At this point I decided to Google Noda’s name, and found both an unrelated Japanese-American nisei painter with the same name (crazy coincidence!), and an English biography on the website of a museum which carries his work. This biography is curiously whitewashed of his Communist adventures, although according to Chambers, they occupied a great part of his life after 1934.

Here is how the museum describes his later life:

Noda didn’t adhere to authority or strive after a false reputation. He was a humantistic [sic] painter who turned his eyes to the world of the mind and continued painting the working class, immigrants, circus performers, the unemployed and children from the bottom strata of society. In 1938 he was diagnosed with a brain tumor but continued to paint, holding his eyelids open with adhesive tape. Noda died prematurely at the age of 30.

Seeing such an incomplete biography inspired me to write this quick post to correct the Internet on this matter.

The attempt to establish a Soviet network in Japan failed, and his Tokyo contact John Sherman was commanded to go on to Moscow and barely escaped death there. Noda was also stuck in the underground and it appears he was eventually destroyed by it. Here is Chambers, meeting Noda for the last time:

I saw [Noda] only for a moment [in 1938], to give him the address [of his next meeting place]. I did not ask, of course, where he had been since I had sent him on to a hotel in Southern France. Before Noda had been alert, somewhat as birds are, as if in him mental and physical brightness were one. Now he seemed a little faded and tired. Our brief meeting was stiff… I suspect that Noda was so silent because, had he begun to speak, the words that came out would have been: “Oh, horror, horror, horror!” … In 1939, the New York Times published his rather impressive obituary. In Tokyo, the promising Japanese-American painter Hideo Noda had died suddenly, of a “cerebral tumor.”

John Sherman refused to testify on the subject of Noda, pleading the fifth. This means that there is no information on Noda in English that does not either derive from Whittaker Chambers’ account or whitewash his Communist background. There is no Japanese-language equivalent to Google Books that would allow me to research this quickly, but none of the Japanese accounts of Noda online mention his underground work, except for one blog post which hints vaguely at “information collection”, but fails to mention any of his multiple trips overseas during the treatment of his “brain tumor”, if indeed he was diagnosed with a tumor at all. It is striking that the museums that hold his work do not realize what he was doing when he died, but it seems that Witness really is our only standing witness to the Communist underground at least on this detail.

Posted: January 3rd, 2012 | World Peace 3 Comments »

In the old days they didn’t have cars. The shortest way to get from Yamauchi to Imari was to walk over the mountain. That’s right, walk over the mountain. You know how many trail markers they had? Just one. This one.

Posted: December 11th, 2011 | Japan, Travel 3 Comments »