As we students of the Takenouchi Documents already know, when Moses rode a UFO to Japan he presented the world with a second set of Ten Commandments. Actually, it was simply the same stone tablets, but he had forgotten to show the Israelites what was written on the back side. Anyway, here they are in English for the first time:

Honoring the law of Romulus, 60th generation descendant of Adam and Eve

Omoyakami Taruwake Toyosuki Emperor Hitsuki 200 Years — 10 Commandments of Moses

1. Thou shalt worship the gods of Heavenly Omoya Japan

2. Thou shalt worship the Omuya Hitsuki Emperor

3. Thou shalt not disobey the Sun Kami, for if thee do thou willst be smited

4. Thou shalt not disobey the law of the emperor of the Heavenly Omoya

5. Thou shalt not disobey the emperor of the Omoya

6. Thou shalt protect the law of the five races of Ajiti

7. Thou shalt not disobey the law of the Omoya of the Ajitikunists, the decided law of Ajitikuni

8. Thou shalt rescue the red and correct the black of heart

9. Thou shalt inform thyself of the stories of other kami

10. Thou shalt worship the spirit kami — Twice, Āmen!

The law of all nations. 10 Commandments of Moses, Mount Sinai

You can visit Moses’ grave in Ishikawa-ken.

Posted: October 26th, 2010 | Japan

Tenrikyo and Christian Science are both faith healing religions founded by women in the late 19th century on the basis of direct revelation from God. Both lived in an age where the powerful concept of faith healing was being crowded out or suppressed by more controllable, institutional behaviors, these being “Churchianity” in America and “non-religious Shinto” in Japan. Both attracted highly intelligent individuals from outside the mainstream, who eventually gave both groups unexpected relevance in 20th century society. Here is a brief sketch of their development from someone who is only somewhat acquainted with the church histories.

Splinter groups

It was expected that Tenrikyo Shrine of God and foundress Oyasama would live to 115 years per her own prediction. When this did not happen there was confusion in the movement. Many believed in the 天啓待望論 (tenkei taibou-ron), the doctrine that a new Shrine of God would be appointed at the end of Oyasama’s 115-year era. At least two splinter groups formed when the 115 years were up in 1913: Oonishi Ajirou’s Honmichi, and a group called 茨木一派 (Ippa Daidou). I think there were others, but this is not clear to me. Individual Tenrikyoists, dissatisfied with the direction of the church, also founded basically unrelated groups like Moralogy.

Christian Science also splintered after its founder’s death. The Christian Science Parent Church was founded in England in 1912, two years after Mary Baker Eddy’s death, and gained a small following in America as well. Like Honmichi, the Parent Church emphasized its leader’s position as the next inheritor of revelation. In this case, leader Annie C. Bill wrote a book called Science, Evolution, and Immortality which supplemented Science and Health. Unlike Honmichi, this group is now completely extinct. This information comes from a fascinating 1926 encyclopedia of religious bodies issued by the U.S. Census, which also includes an early official recognition of non-Christian “religious groups”.

Making faith healing relevant

The paths taken by both organizations in the 20th century are fascinating as stories of how marginal spiritual groups plant themselves in their home societies. Christian Science, of course, is known through the United States for two things: its reading rooms, which dot main streets throughout the country, and the Pulitzer-winning Christian Science Monitor, propped up entirely on Christian Scientist donations for many years with scarcely a mention of religion in the paper itself. Tenrikyo has worked the same way: in Japan they are known throughout the country for Tenri University, which has a famous judo team, and on a lesser scale for the excellent Tenri Hospital and Tenri City in which both organizations are located. If you ask an American about a Christian Science Reading Room, they will often be familiar with its existence as a neighborhood staple even if they don’t know exactly what it means; Tenri University has the same associations in Japan.

More to come as I research more.

Posted: October 10th, 2010 | Secular-Religious

You will recall my quote of Spengler in my article on ahistory, where he asserts that India had no history, and I clarify that it instead had a resistance network of stories which prevented the creation of history. I think this was a good thing with regards to Indian society. Now I have learned that there was a very interesting person who thought it was a bad thing:

Now, sickening as it must be to human feeling to witness those myriads of industrious patriarchal and inoffensive social organizations disorganized and dissolved into their units, thrown into a sea of woes, and their individual members losing at the same time their ancient form of civilization, and their hereditary means of subsistence, we must not forget that these idyllic village-communities, inoffensive though they may appear, had always been the solid foundation of Oriental despotism, that they restrained the human mind within the smallest possible compass, making it the unresisting tool of superstition, enslaving it beneath traditional rules, depriving it of all grandeur and historical energies.

Indian society has no history at all, at least no known history. What we call its history, is but the history of the successive intruders who founded their empires on the passive basis of that unresisting and unchanging society. … England has to fulfill a double mission in India: one destructive, the other regenerating the annihilation of old Asiatic society, and the laying the material foundations of Western society in Asia.

Karl Marx, 1853.

What “grandeur” did Marx see in a potential India? What are the “historical energies” that he believed needed to be loosed on the country? Well, I guess I can answer that question from what I read of Marx. Still, it certainly points the political compass of the ahistorian in a new direction.

Posted: October 2nd, 2010 | Postcolonialism

高野聖 Kōya hijiri

A brand of merchant from Mount Kōya, usually from the criminal class. Often improperly translated as “Buddhist missionaries”, sometimes with the claim that they spread some Buddhist beliefs, which is at best a vast exaggeration of the facts. In reality, although they were approved by Kōya authorities, the approval chiefly permitted them to make a living as traveling salesmen, perhaps playing some music or dancing on the side.

English Wikipedia amusingly links their Kōya hijiri article to another term, yadōkai, which they describe as follows: “Yadōkai (夜道怪) is a derogatory term for Kōya hijiri. They were considered to be a kind of supernatural creature, wandering at night, damaging property, injuring people or kidnapping children. As shown in Gegege no Kitaro. Kōya hijiri served as itinerant traders, were well informed about life, and deceived local people.”

解毒圓 Gedokuen

A brand of medicinal herb sold by a pharmacy named Dōshōan 道正庵 under exclusive contract from the Sōtō Zen sect of Japanese Buddhism; it was sold to Zen temples as well as the general public. Mixing Gedokuen with various other herbs or rubbing it on yourself was guaranteed to cure almost any ailment, and it was advertised as a panacea. The story went that the recipe for Gedokuen was received by Dōgen from the white fox kami Imari, and Dōgen went on to order Dōshōan to sell the drug throughout Japan. This story was fabricated in the 1700s and tacked on to the first printed biography of Dōgen, which created a fairly confusing narrative where Dōgen’s whole life built up to endorsing a magical drug. However, the Sōtō Zen sect apparently approved of this activity. It continued until 1945.

Another famous panacea of the Tokugawa period was called Kintaien 錦袋圓, and was also invented by a Buddhist sect, allegedly communicated to a young monk in a dream by the sect’s founder Gyōtei.

般若湯 Hannya tō

“Water of Perfect Wisdom”. A term for alcohol used by Japanese Buddhist monks, implying that drinking this very special water will open you up to the wisdom of Buddha. Drinking alcohol is a violation of one of the five precepts of all Buddhist monks and is grounds for expulsion from the sangha, except in Japan. In the Meiji period, many temples had signs posted at the door warning monks not to bring alcohol inside, but hannyatō would be carried in regardless. Contrary to the American scholarship on Japanese Buddhist jargon, this euphemism is not meant to cover up the fact that monks are drinking alcohol. Rather, it is a sardonic term, and many Americans seem to misunderstand the deadpan tone in which the joke is told (e.g. “if you call it hannyatō it’s okay”). It is still used today.

There are various other Japanese Buddhist terms which had secret slang meanings in the Edo period, most of which are not fit for publication on a family blog: 念仏講 nenbutsukō, 阿弥陀経 Amida Kyō, etc.

三種の浄肉 sanshu no jōniku

“The three kinds of pure meat”. It is often claimed that the precept prohibiting killing renders all Buddhist monks vegetarians. However, in Japan (as well as China and Korea, in this case) circumventing this rule has proven all too simple. There was a sutra somewhere, nobody knows quite where, that says that there are three ways to make meat pure:

- You didn’t see the animal being killed.

- You don’t know whether it was killed for your sake.

- You didn’t hear whether it was killed for your sake.

These exemptions are so ludicrously huge that meat is pretty much fine. Thus everyone in Japan has an in-joke to laugh about, and gaijin vegetarians who come to a temple seeking Japanese vegetarian food are oftentimes naively disappointed (or charged exorbitant prices for shōjin ryōri).

僧兵 sōhei

“Warrior monks”, or more accurately the military forces of temple-states. There are entire books written about this subject, but suffice to say, the majority of “monks” from A.D. 950-1600 were not above setting fire to rival temples or pillaging local villages. Usually they lived in temple towns, 門前町 monzenmachi, and not within the temple itself. Most notably found in Hieizan Enryakuji (controlled western Biwako), Kyōto Hongwanji (distributed throughout the provinces), Kōyasan Kongōbuji (controlled Kii), and and Kōyasan Negoroji (controled Kii; notable for manufacturing muskets).

Posted: October 1st, 2010 | Dharma

Have you ever had a Japanese person come up to you on the street and tell you about the oldest XYZ in Japan which you can find in this particular area? This happened to me for the second time today. My friends and I were looking vaguely out at the harbor in Dejima, and a complete stranger–naturally, an ojisan–approached us and talked about the oldest Protestant seminary in alllll of Japan which used to be on Dejima but was moved somewhere else. The first time was on my study abroad, when a stranger, also an ojisan, sat next to me on the train holding a binder full of laminated newspaper clippings, ascertained that I didn’t know enough Japanese to comprehend his vital message, and went to tell my program director about how this particular area of Kyoto was in fact the oldest human settlement in Japan, but had been covered up by an official conspiracy.

I reflected on these unusual events after hearing my professor friend say this evening, “It’s not that Japanese people don’t have an opinion about history, but we don’t speak about our opinions.” This is both true and false in extremely important ways. As I understand it so far, not quite knowing enough Japanese to read Beat Takeshi’s History of 20th Century Japan, there are five ways in which Japanese people are interested in history. The first is the usual, bookish memorization of names and dates as taught in middle schools, and keeping any underlying narrative to oneself. The rekijo seem to be mostly of this first category. Indeed, this normal mode of history is purely about facts and has nothing to do with opinions other than those of the “rules-sucks” type.

The second is the myopic obsession with blaming people from history for the problems of today, which has caused endless Japan-bashing. The third is the equally myopic defense of every Japanese person in all of history against the attacks of the critics, which is just as lame. These two types of interpreting history are based on very deeply held opinions, but the one thing people hate to do in these discussions is admit they have an opinion; thus they will present their opinion as an unbiased exposition of the facts, even when this strains credulity, which only adds rancor to the discussion.

The fourth type, just to acknowledge its existence, is the actual opinionated narrative that directly contradicts my professor friend’s statement. I am guessing Beat Takeshi’s book is one such example, based on the Amazon reviews. It is nice to know what Japanese people think about their own history, and even nicer to read it in a book instead of painstakingly exacting it during a conversation. These books are still rare, though.

But the fifth type most interests me, because it is absent from Western historiography. There are a large number of middle-aged men in Japan (and perhaps a rekijo or two) who have scientifically and accurately determined that some whatsit in their hometown is the OLDEST WHATSIT IN ALL JAPAN, and must get the word out about this old whatsit to the entire world, especially notifying any foreigners that happen to come pass through the area. Of course, every country in some way has a mania for the ancient. The only country that has not traditionally obsessed over its own age is India, and even that is now changing. But in Japan this manifests in a unique way. Perhaps these ojisans are continuing that great kokugaku quest to find the purity of ancient times. (Speaking of which, doesn’t that make this historiography predate the other four kinds of historiographies? You know, I think it does!) Perhaps they just have too much free time on their hands, and spend every Sunday patrolling for possible recruits to their cult of the old thingamabob. Who knows? It is something to explore if you ever encounter it in Japan. Just learn Japanese first, because they often don’t know English.

Posted: September 26th, 2010 | Kokoro

I was surprised to see my town in the national news today. Even though I’m in Japan and don’t read the Globe, while I was looking through my Twitter updates I learned that Wellesley Middle School students participated in a visit to a mosque as part of a social studies program, and some of them engaged in “prayer” during the visit. This sparked tired, fake outrage from an anti-Muslim rightist group absurdly named “Americans for Peace and Tolerance”, which claimed that their “Inside Video Captures Kids Bowing to Allah“. Of course, there was no cover-up performed, and the video of five unnamed children was released without permission from any of the families involved, solely to stir up controversy. The insinuation the group was making was that naive liberal Wellesleyites allowed their children to be converted to a pagan cult of genocide during a 30 minute visit to a mosque, which makes sense only in the alternate universe that the right wing lives in.

No, I’m not interested in the fear-mongering, nor do I think anyone is at fault for allowing kids to imitate a religious service during a field trip. What interests me is why these students decided to “pray” and what background they might be coming from. See, reading this report takes me back to my days at Wellesley Middle School. I was pretty much an outcast then, but I loved learning about other cultures, and a trip to a mosque would have been the ultimate cool thing. If I had gone, would I have imitated the prayer?

Consider the mental life of an average American middle schooler. Middle school is social hell in every country on Earth– I’m typing this from a Japanese middle school and you can feel the social pressure in the classrooms. Kids are much more likely to make decisions based on their status as an insider or outsider than what their parents or teachers are telling them. Furthermore, if there is such a thing as an ideal Democrat or Republican, middle school is where you will find such a person. Just think back to how you thought about politics in middle school– America is all about civil rights and liberal ideals! No liberal project could go wrong! Actually, I’m finding it hard to distinguish between middle school and what passes for political commentary in America. Anyway, this could be a dangerous naivete outside of Wellesley, but in that town it’s just kind of cute, and in this case inspiring.

There were five boys praying in the anti-Muslim group’s video; all of them had voluntarily left the rows of students and joined the rows of the congregation. To cover all the possible bases, let’s say that one of the kids was Muslim, two of them were his friends, and two more simply joined in because they wanted to. (I’m not claiming this is actually the case.) It is bizarre to claim that a devout Muslim cannot pray at noon, as he would probably do anyway every day at school, just because he is on a field trip; I will ignore that altogether. If that Muslim had two close friends, under the power laws of middle school they would be strongly compelled to join in just so that he wouldn’t be alone in his choice to pray. This choice would have nothing to do with their understanding of Islam. Can you really claim that supporting a friend by imitating religious ritual violates the separation of church and state? What if the imitation was meant to mock a religion– does that violate that separation? Really, this would be a strange area for the face of secularism to intervene.

The final case, and most likely, is that the kids were imitating without much of a thought whatsoever. This reminds me of a story told by a professor named Tomoko Masuzawa about her study abroad program in America. Her host family was Catholic, and took her to Mass, the meaning of which she did not understand; comparing it to activities in Japan, she might have thought it was a festival or something like that. At Mass she received the Eucharist. She barely gave it a second thought. But later, she went on to study religion, and only then learned that receiving the Eucharist is not something that everyone in America does, but rather signifies that one is a member of the Catholic Church in good standing, and opposes Protestants and so forth. Isn’t what she did an honest mistake, not knowing symbolism? Regardless of whether she accidentally engaged in something “religious”, did she actually become a Catholic by following the patterns of her host family? I don’t think so.

I think it’s just as likely that, having just heard a lecture about Islam, the boys understood that their actions were part of a larger fabric called Islam, but simply didn’t care. They’re only kids, and if there’s any time to blamelessly try out the activities of foreign cultures it would be on a middle school field trip (which makes the covert recording of the video just that more cruel). It could have all sorts of unrelated, secular meanings for them: maybe it made them feel sort of rebellious, or separated them from their hated peers, or made them feel in touch with this cool thing called “Islam” that all the evil Republicans hate. If four people around me had been doing that on my field trip, I wouldn’t have felt any qualms with joining in. After all, it’s not something you get to do every day.

All I’m trying to say is the least likely thing for a middle schooler to do is to spontaneously convert to a new religion on a field trip; I have not read any reports of such a thing happening in Wellesley. It is, however, incredibly likely that kids were imitating prayer for the same damn reasons that kids do anything in middle school, and that their action sparked a rabid right-wing video and an apology from the principal is a clear symptom of a poisonous political climate.

(P.S. In the antiquated cosmology of Christianism, of course, a whole different thing is going on: Christian children are being tempted to worship at idols, which, regardless of their own understanding of their actions, will deliver them to Hell. Let us hope that nobody outside the walls of “Americans for Peace and Tolerance” actually propagates such a medieval belief. Here in real life, participating in a culture without knowing what it means does not change your attitude whatsoever; being told that you are a bad person for doing so just might.)

Posted: September 24th, 2010 | Secular-Religious

I was at the cigar store in Harvard Square yesterday and saw a wonderful book on their shelf called The American Barbershop: A Closer Look at a Disappearing Place. It was an extremely insightful look at what makes a barber shop a real place for men, why people go there, and what happens there. Another book in this vein, discovered on Amazon when I got home, is Do Bald Men Get Half-Price Haircuts?: In Search of America’s Great Barbershops. I recommend both of these books to people in search of what I’m about to describe, especially the former. But the first was written by a photographer, and the second by a freelance writer. Neither book would be considered a “scientific” look at the barber shop in the way that a peer-reviewed journal article would be.

Read the rest of this entry »

Posted: July 15th, 2010 | Book Reviews

I am tired of hearing about religion and evolution. I have read about the subject since I was 13. So, let’s look at a much more fascinating subject: religion and archaeology. Actually, this subject is written about far too little. Anyone can give you a long list of reasons why students must learn evolutionary biology properly and not buy into old myths instead. But who has discussed why archaeologists are so interested in old artifacts?

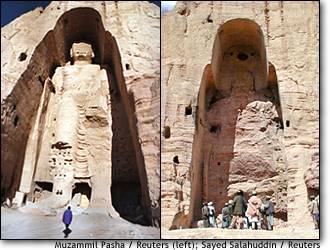

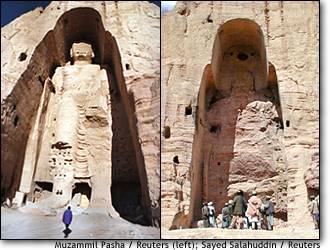

In 2001, the Taliban destroyed some gorgeous Buddha statues in Bamyan, Afghanistan. This evoked outrage all over the Western world; through our international media, soon the whole world had heard the story. What provoked such universal condemnation? Obviously there wasn’t some secret Buddhist lobby behind the scenes. Their purely scientific value was minimal, as they had already been examined. Was it because they were such beautiful statues, or so big? I’m sure there was someone who would try to argue this, but it is easy to disprove. Later the same year, the French government destroyed an enormous statue of a cult leader in Castellane, France. This elicited precisely no outrage from anyone, even though a cult spokeswoman made an explicit comparison between her group’s statue and the Bamyan Buddhas.

The Islamic ideal that provoked the destruction of the Buddhas is easy to identify. In Islam, as in humanism, the story of humanity is a path from darkness to light. But the Islamic message, especially in its modern and unstudied forms (c.f. the Kitab al-Asnam for a medieval counterexample), is much simpler than the humanist. In the past Age of Darkness, the story goes, people worshiped idols and killed each other for stupid and barbaric reasons. In the current age, people move away from profane habits and towards purer and more divine activities, and treat each other with dignity and justice. There is no need for doubt about social aims or cross-cultural dialogue, because the only message that is needed is all contained in the Qu’ran.

The Western ideal that led people to condemn the destruction of the Buddhas while ignoring the cult statue is somewhat harder to define. Looking at both these cases betrays the actual interest we have in these Buddhas, which none of us had ever seen before. They were important because they were relics of an ancient culture, and were a significant marker of human achievement from that age. We can’t name one specific faith that leads us to treasure these relics, because secularism specifically denies assigning names to its ideals. But in the legally encoded humanist language of the United Nations, it is easy to identify the parallel term: “World Heritage”. We believe that everyone should have knowledge of and access to the historical artifacts which tell us about our shared humanity.

Looking from the outside in at these two cases, I do feel a little conflicted. Personally, although I am Buddhist, I think the cult statue was much more interesting, a veritable monument to the unstoppable creative force in humanity. Given the resources of the modern age, a small cult was able to build a ridiculous tribute to an individual nobody else cared about. The Bamyan statues, on the other hand, were just a few Buddhas among many, and we all know what Buddha looks like. I can understand why the Taliban decided to blow them up; they must have represented to those clerics a history of outside domination, and were physically two big idols towering above them in a position of authority. Sure, it was an arrogant show of personal insecurity, but haven’t we all felt insecure at one point or another?

I think the proper response to events like this is not to unilaterally condemn one group and praise the other, but to understand where humanist beliefs like “World Heritage” come from, and why they are necessary for the future of humanity. Too often, shared sentiments like these go unanalyzed in the West, or even ignored entirely; even recognizing the simplest things, like “nobody wants war”, can stir something in people’s hearts, as it did in the case of Samantha Smith. By explaining where we come from, we can invite other people to understand us.

Posted: July 12th, 2010 | Secular-Religious

In the Land of Invented Languages

by Akira Okrent. Spiegel & Grau, 2009. Buy it on Amazon

This book is relentlessly fun to read and written from the perfect point of view. Okrent is a practical linguist, who harbors no fantasies of a universal language, but is yet open-minded and deeply interested in the people who do invent languages, and why they make them. I think the most important lesson I learned from it is why Esperanto is fun, and people should make an attempt to learn it.

Back around 1998 I stumbled across the website Learn Not to Speak Esperanto and had myself a good laugh at the people who would try to promote this clumsy language. Why, it’s like Italian written in Eastern Polish! Any other constructed language is better than this one! What a joke! Already I was thinking about it the wrong way, but even though I examined constructed languages many times over the intervening years, I never was able to approach it in the way Okrent presents it for our edification.

Everything about Esperanto makes it more interesting to learn than its competitors. First, despite its weirdness as a language, it’s easy to learn; and once you learn it, you can make new and funny uses of the weirdness to delight your fellow learners. Second, it’s fun to speak in, as opposed to its predecessor Volapük. Third, and finally, the Esperantist culture is one of promoting universal brotherhood and is so lively that it makes you want to speak the language more and more.

Consider the fundamental differences between the way language is thought about in Esperanto as opposed to its competitors, as pointed out by Okrent. One of the example texts that Zamenhof used the original Esperanto books is a letter to a friend, which starts, Kara amiko! Mi presentas al mi kian vizaĝon vi faros post la ricevo de mi a letero, or “Dear friend! I can only imagine what kind of face you will make after receiving from me this letter.” Clearly the intent of this passage is not to make a perfect language, but to puzzle and delight the reader. Reading this example, perhaps more than a few Esperantists sent off some puzzles to their friends as well. In the context of thinking about language as puzzle, we do not need to strive for perfection. But if we do strive for perfection, then we start to forget about how much fun learning a language can be.

The way Esperantists congregate and talk to each other also makes the language more enjoyable. The chief argument against Esperanto, of course, is that English is already a world language. But contained in English, for non-native speakers, is an undeniably bad implication. They are forced to learn English, whether they like it or not, to conduct business with native speakers; and they will be mocked if they speak it poorly, since it has a large native speaking population who more often than not simply assume other people have learned it for their sake. Now consider how people learn Esperanto. It is learned by choice, outside of school, as a “useless” but fun hobby. (Isn’t it interesting how the most enjoyable endeavors in modern society are “useless”?) It has no business application, but is only used for sharing humanity. When the learner comes together with other Esperantists, there are very few or no native speakers, and everyone treats each other as equal. At a conference, the Esperantists genuinely encourage each other to keep it up, and enjoy themselves by singing songs, dancing, and so forth. Conferences receive letters from other parts of the world, for no purpose other than to let them know that they can communicate in Esperanto in any country.

Finally, as an English speaker I can stay at any classy hotel in the world when I travel, but it will be a lonely stay, and English will be part of the room service rather than an enjoyable endeavor for the staff. As an Esperantist, not only could I have lodgings in the homes of fellow Esperantists, but we would have a hobby to talk about and a good reason to become long lasting friends.

In short, this sounds like something I would very much like to do; but business interests are forcing me to learn Japanese first.

Posted: July 1st, 2010 | Book Reviews, World Peace

Maybe not a lot of people know that Twitter in Japan has its own vocabulary. Talking with your buddies on Twitter is kind of like meeting them on the street.

Read the rest of this entry »

Posted: June 25th, 2010 | Japan