Learning about Ise at Kogakkan: Days 9-10

While we learned about and visited a large number of places over the past few days, I’m going to use this post to focus on the subject of onshi 御師. The existence of pilgrimage promoters called onshi had been hinted at in previous classes, and I was under the impression that these people were something like travel agents. This was also the impression of our tour guide for today, who labeled onshi estates as “hotels”. In fact, as the medievalist Okada Noboru 岡田登 explained to us this morning, the name onshi is shorthand for the mind-boggling distance between the ancien régime of 1867 and the New Japan of 1877. Onshi were the literal center of pre-modern worship at Ise, and a key aspect of Japanese feudalism. In an age where the Jingū was closed to everyone but the Emperor, the population of Japan, rich and poor, registered themselves with religious gentry called onshi in order to forward their prayers to Amaterasu. In a word, the onshi were Japan’s First Estate, and Ise was once a sprawling, aristocratic Vatican.

I stole this illustration from a corporate magazine called Obayashi Quarterly, I hope they don’t mind. Pictured here is the estate of an onshi named Mikkaichi Dayū Jirō 三日市大夫次郎, which means something like “Joe, Lord Wednesday Market”, certainly not a name I’d associate with nobility. Some of the onshi had strange names; one of them was called Lord Dragon. Mikkaichi Dayū’s parishioners amounted to 350,000 to 500,000 households, meaning that he likely had over a million people on his rolls who exchanged their “first rice” fees (初稲料 hatsuhoryō) for the right to have prayers forwarded to the Jingū, and the possibility of staying at his estate and witnessing a kagura sacred dance if they were ever able to save up the money for a pilgrimage. Here’s the shocking thing; the kagura dance was not performed at the Jingū itself, but was in a special building towards the back of this estate. Furthermore, the ofuda talismans that onshi sold to parishioners were not from the Jingū, but were produced completely by the onshi, in their capacity as shrine priests. In short, the onshi were religious institutions providing the public’s sole line of access to the Jingū.

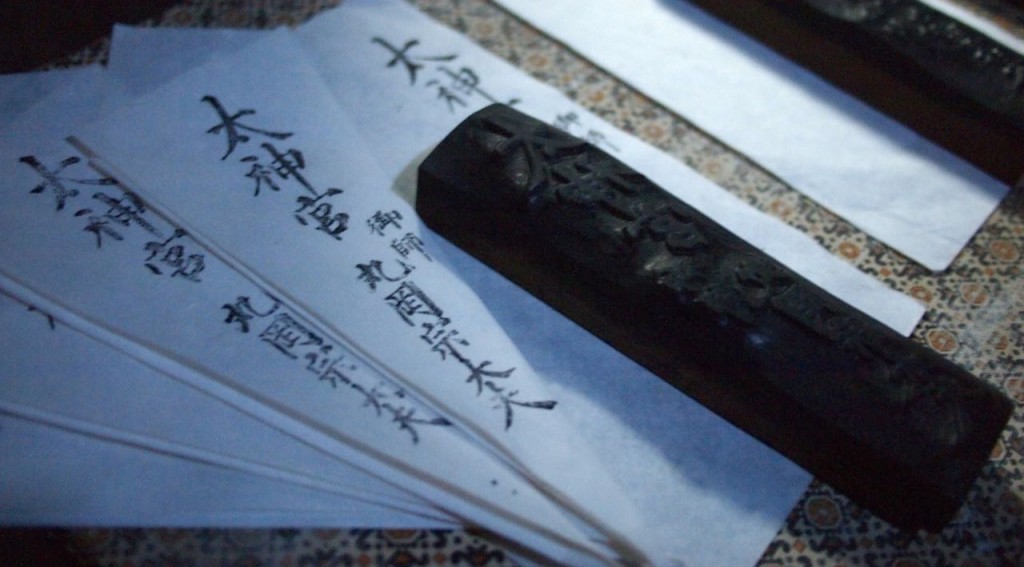

Pictured: The original stamp used by a Gekū onshi to produce ofuda, along with several examples. The sticks that one finds inside ofuda would also have been supplied in-house.

Okada-sensei painted a rather dire portrait of the state of knowledge we have about onshi. He expounded at length on the fact that nothing was saved when the onshi system was abruptly abolished in 1869. A system that had received the support of 80-90% of the Japanese population suddenly vanished, and all the gorgeous estates had no means of upkeep. Like the suddenly disinherited samurai Shiba Ryōtarō describes in Clouds Above the Hill, the onshi had no choice but to move away and find new jobs, but where samurai families had houses scattered across the country, everything the onshi had done was centralized in Ise, which instantly transformed from the noble headquarters of an established religion to a backwater fishing village. Hundreds of years of detailed records, detailing up to 700 years of Shinto customs, were generally sold to paper mills where they were turned into tissues and toilet paper. In many cases we do not know how onshi families came into existence or how they became chosen by their patrons.

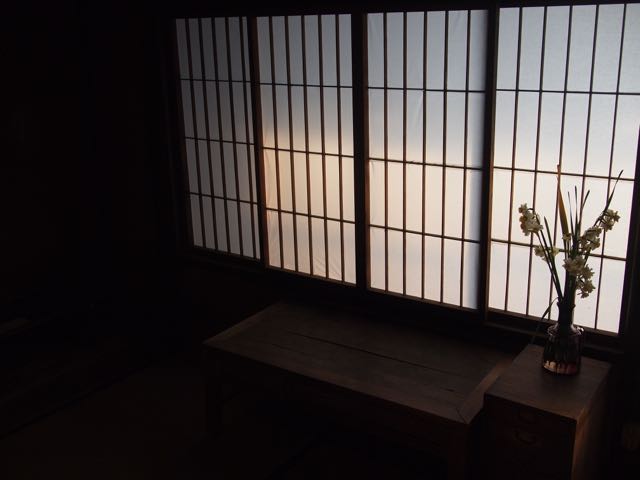

Many of the abandoned onshi estates were turned into rubble when the Americans bombed Ise in 1945, and others were demolished in the postwar years due to their extreme age. In 2015 there is only a single onshi estate still standing in Ise. This is the Estate of Maruoka Sō Dayū 丸岡宗大夫邸, which happens to have been built in 1866. It is currently owned by the 18th Maruoka Dayū, Maruoka Masayuki 丸岡正之, who works as a carpenter. Maruoka receives no money from the city or prefecture to pay for upkeep on the estate. He does not make enough money to keep it open, but has spent many years keeping it intact and opens it up for special occasions, such as when a group of foreigners are visiting. He says that his grandparents loved the old house very much and preserved it when many other houses were left to rot.

Pictured: Micchan stepping into a front room.

As I said, the onshi system lasted almost 700 years. (General Electric and Disney will be quite lucky to last that long.) It began as a replacement for the Saiō, when the Saikū was falling into disrepair and the Imperial household was no longer able to provide the Jingū with reliable funding. In 1181, Minamoto no Yoritomo, the founder of the shogunate system, came to Ise personally and petitioned a 4th rank Gekū priest (konnegi 権禰宜) named Watarai Mitsuchika 度会光親 to make a prayer on his behalf. It was the first time in the Jingū’s 700- to 1100-year history that a prayer was offered on behalf of someone other than the emperor, and it was the first time someone from outside the Imperial family had come to Ise for that purpose. As far as legitimizing his authority went, Minamoto no Yoritomo was both bold and clever.

He was also a trendsetter. As more estates in Japan fell into private hands, leading to the feudal or manor system (荘園 shōen), emerging landlords dedicated portions of their land to the Jingū specifically, in order to get the same divine favor that Minamoto had secured. This land was called mikuriya 御園 “sacred manors” or mizono 御厨 “sacred kitchens,” i.e., places where offerings were prepared. Similar to the medieval Church, the Jingū ended up inheriting and possessing large amounts of land in this way. The Gekū priests who made prayers in exchange for these offerings were called on’inorishi 御祈祷師, or “sacred prayer teachers,” later shortened to onshi. A similar system was already in place at Kumano, and later many shrines and Buddhist temples had such teachers, usually called oshi outside of Ise.

By 1383, the Ise onshi were serving parishioners in every part of the country, from Ezo (Hokkaido) to Kyushu. The onshi multiplied into the hundreds and they began purchasing parishes from each other and fighting over patrons. As we learned way back on day 1, the communities they supported, called Yamada and Uji, were basically at war with each other from 1400 to 1600, causing the only interruption of the shikinen sengū in Japanese history. Three classes of people served as onshi. First came the officiating priests called konnegi, who were usually called Dayū 大夫 after their aristocratic rank and often called ji’nin 神人 or “god people” in written documents. Lower level religious functionaries, also able to offer prayers, were called shin’yakujin 神役人. Finally, ordinary merchants, through some intervention that Okada-sensei did not describe, were able to become onshi at some point; perhaps this was how we got to Lord Wednesday Market above. [edit: Chieda-sensei clarified that the merchants, including Maruoka Dayū, purchased their titles.] All levels of onshi had to employ bureaucrats fluent in all the different dialects of pre-modern Japanese, in order to grant prayers and do business with people from across the country.

Uji-Yamada was at last pacified, and the onshi system officially regulated, with the rebirth of the shogunate in the 1590s, and the system reached its peak in the 18th century. Every onshi was at the head of an enormous nationwide network that had its luxurious headquarters in the sacred city of Ise but went all the way down to itinerant travelers bestowing ofuda as they did their rounds in rural villages, and selling goods such as astrological calendars from Ise or beauty products (usually made from mercury… oops). As noted above, up to 90% of Japan’s 30 million people were members of an onshi group in some way or another; those with no membership at all were considered in a vague way to be outside the reach of civilization.

In 1724, the Gekū peaked at 615 different onshi lords, and in 1777, the Naikū had a much smaller peak with 271 onshi. Following this, the groups slowly consolidated their power. The Maruoka Dayū estate that we visited today contained rare surviving testaments to this power. First, we have this hengaku 扁額, produced to memorialize a kagura dance conducted by the onshi and his parishioners in 1865.

It looks like a pretty ordinary engraving on wood… but when our tour guide Chieda-sensei saw it, he remarked, “pretty bold!” Why is it pretty bold? Because it reads “Great Jingū of Amaterasu Ōmikami” 天照皇太神宮, but in fact, this onshi was serving the Gekū, which honors Toyouke Ōmikami, god of agriculture and food preparation, and most certainly not Amaterasu. The ofuda stamps at the Maruoka Dayū estate seem to testify that as the Amaterasu cult picked up steam in the mid-1800s, the onshi around the Gekū simply began proclaiming that they were authorized to offer prayers to Amaterasu. But this is something it’s impossible to know for sure, because so many records were destroyed. Now, some more proofs of power.

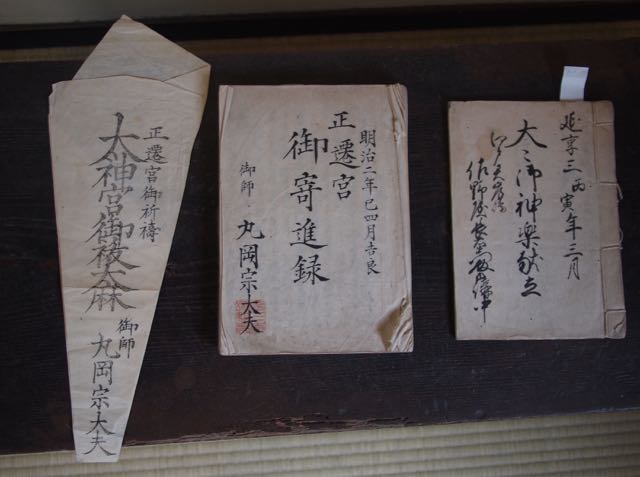

On the left here is one of these newer ofuda; it appears to come from the “Great Jingū” (Gekū? Naikū? Both?), but was actually produced on site by the Maruoka Dayū. [edit: According to Chieda-sensei, he was not supposed to be able to do this, since he was only a merchant and not a priest. But Maruoka-san insisted that his ancestors made the ofuda themselves. Another mystery.]

Next to the ofuda is a very long list of people who gave money to the onshi in honor of the shikinen sengū (the money did not pay for the sengū itself, but apparently they simply solicited every time this happened). On the right is the reward provided to parishioners who came to Ise: a travel schedule for a deluxe package pilgrimage, with three days of meals and events surrounding the kagura dance. This may look like gross profiteering from a modern perspective, but in fact this onshi was performing a sacred duty for his parishioners. He was their link to the Jingū, as they were not allowed inside themselves. Only after the abolishment of the onshi system in 1871 were the gates opened and a kagura hall built inside the Jingū itself. By the way, if you go to Ise to see a kagura today, you will see it performed by beautiful young women. But the dance you would have seen at an onshi estate up until 1871 would have used older women, often in their 50s and 60s, with decades of practice.

Ten luxurious gates of a style reserved for titled gentry are scattered here and there in the city of Ise, along with a few beautiful antique rooms comprising the partial remains of the Maruoka Dayū estate, and that is all that remains of the onshi system that once ruled this city. Once, Maruoka Dayū boasted a nationwide network, but now his heritage is hanging by a thread; the building seems ready to collapse, and the government will not pitch in for this last testament to 700 years of history. The friends of the owner have set up a Facebook page to encourage people to preserve the estate, and that’s about it.

Posted: March 4th, 2015 | Kogakkan